Author: Lola Gueguen

Estimated reading time: 9 minutes

If you’ve ever wondered, “Can my child really learn a new language if we don’t speak it at home,” the answer is yes. Children are remarkably capable of acquiring new languages in immersive bilingual settings, even when the language isn’t spoken at home.

Table of contents

While you may notice moments of language “mixing,” where your child blends words from both languages in the same sentence, rest assured that this is not a sign of confusion or failure to learn either language. Rather, it’s a normal part of development and is a sign that your child is growing their linguistic toolkit. Decades of research confirm that children can thrive in bilingual environments, and there are many simple ways parents can further support language development at home, even without speaking the second language themselves.

Inside the FAA’s Bilingual Model

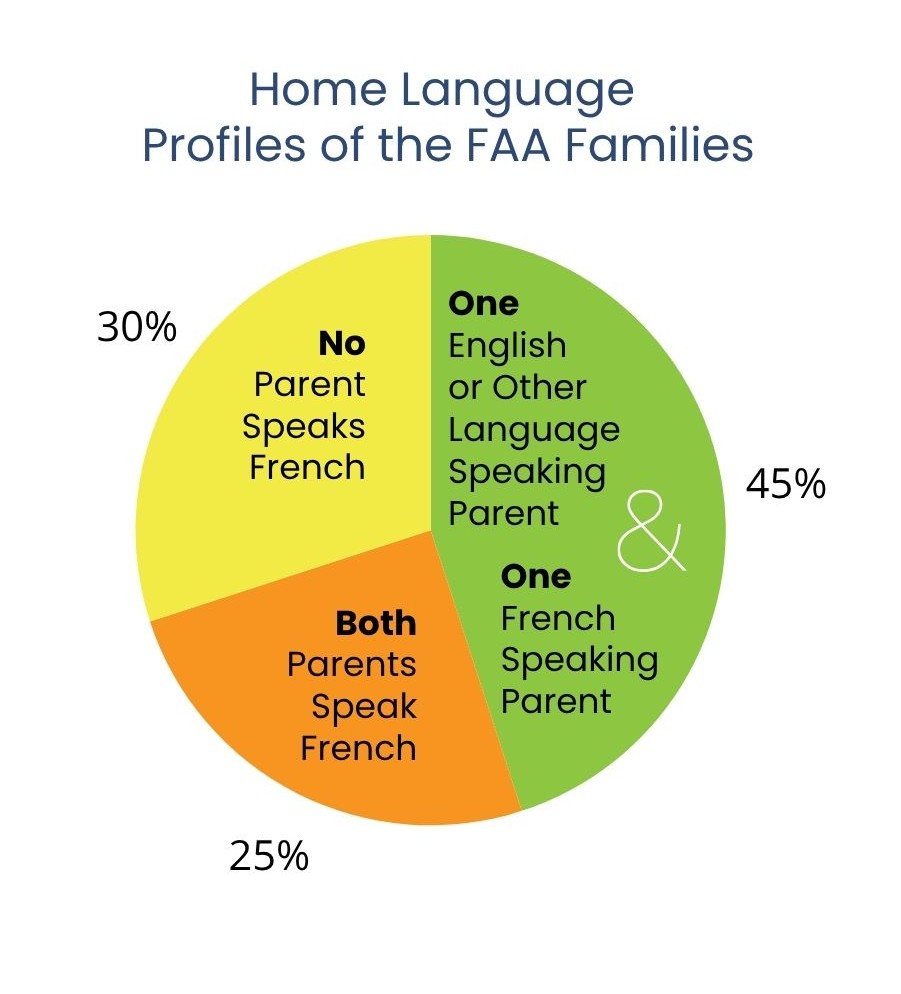

At the FAA, our families come from over 55 nationalities across the three campuses, creating a rich and diverse community. About 30% of our families do not have a French-speaking parent, and the majority speaks English or another language at home. To ensure all students thrive linguistically, the FAA prioritizes a strong bilingual curriculum designed to support both non-French-speaking and non-English-speaking families alike.

A Thoughtfully Integrated Curriculum

Our approach blends:

- American (NJ Curriculum Standards & Common Core)

- French (Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale)

Together, these curricula blend into a thoughtfully integrated bilingual program.

Beginning in preschool, nearly 80% of instruction takes place in French to give students early, consistent, and natural exposure during the critical period for language learning. This also allows English-speaking students to enter the language naturally and confidently, reducing frustration and helping them progress without delays. As students progress through each grade, English instruction gradually increases, allowing both languages to develop simultaneously.

Rather than separating the two languages, we also build bridges between them. Teachers intentionally compare grammar, vocabulary, and concepts across subjects.

Visual Tools That Bridge English and French Grammar

One example is the FAA’s use of the MAK method, developed by Marianne Verbuyt, which helps students visualize and compare the two languages using color-coded tools (orange for feminine, purple for masculine, and blue for neutral English words) This engaging, visual approach helps children form mental connections between the languages and learn to think in both. The MAK method is especially helpful for English-speaking students because it makes abstract French grammar concepts visible and concrete through color-coding and visual comparisons, helping them make sense of rules that are less intuitive and that don’t exist in English.

How Co-Teaching Strengthens Bilingual Learning

The FAA also emphasizes co-teaching, where English and French teachers lead lessons together in subjects like science, math, and oral language, reinforcing cross-language understanding. For students who need extra support, targeted ESL/FSL instruction ensures that every child develops strong skills in both languages. Through this thoughtful and integrated model, students gain bilingualism, cultural understanding, and confidence, showing that children can truly flourish in two languages, even when one isn’t spoken at home. A Teacher’s Perspective on Learning French Without Speaking It at Home

When asked about her experience teaching non-native students who don’t speak French at home, Margot Grayer, the 3rd-grade French teacher at the FAA in Jersey City, noted that these students make remarkable progress. She shared that, much like their French-speaking peers, they are highly engaged in the language, eager to learn, and quickly develop confidence in their ability to communicate in French. She emphasizes that the earlier students begin learning a second language, and the more opportunities they have to practice, the better. Older learners, she notes, may face more challenges due to reduced brain plasticity, increased self-consciousness, and a heightened fear of making mistakes. At the FAA, Margot has seen firsthand how invaluable frequent opportunities for oral practice can be. Activities such as morning meetings, oral language workshops, class presentations, and small-group FSL instruction are among the highly effective strategies she highlights for helping students build their confidence and oral expression skills in French, even when it’s not spoken at home

Supporting Language Learning at Home (Even If You Don’t Speak French)

Even if you don’t speak French, you are just as involved in your child’s education as any other family. Teachers, regardless of the language they use, make every effort to communicate with and understand families, no matter what language is spoken at home. School-wide emails are always sent in English, and important messages from teachers are also provided in English. When something sent home is in French, that means we expect that students can explain and translate it to you. This creates opportunities for conversation at home, allows you to show your interest in your child’s school experience, and helps build their confidence and independence. Additionally, the results from the MAP Assessments, taken at the beginning and end of the year, provide a simple yet valuable way to understand your child’s progress with the English language, highlighting the skills they have mastered, the areas still developing, and how their performance aligns with grade-level expectations in the United States.

Without speaking French, you too can actively support your child’s language growth at home in many simple and meaningful ways. The key is to involve your child in as many opportunities as possible to naturally hear, practice, and interact with the language. Margot Grayer observes that students who take part in fun, French-language activities outside of school, such as playdates with French-speaking families or after-school programs like theater or sports, tend to make faster progress than those who engage with French only through academic work, which can be less motivating. She emphasizes that “exposure to French outside of school hours is crucial” and recommends maintaining some practice over the summer to prevent regression.

Some other ways to encourage language acquisition at home include:

- Reading stories together or having your child listen to French music and audiobooks, through platforms like Lireka and Storyplayr

- Showing interest in French by asking your child to teach new words

- Partnering with the school by attending events, communicating with teachers, and using school resources to pick up new phrases and reinforce learning

- Creating visual labels around the house for items French (e.g., labeling “la porte” for door)

- Celebrating French culture by cooking cultural dishes, visiting museums, or watching French films

- Using simples phrases like “Comment ça-va?” or “Qu’est ce que c’est?” to encourage speaking and listening

- Asking your child each day what they learned in French class

Lastly, trust your child with their assignments. Homework is meant for practice, not perfection. If you don’t speak French and can’t help directly, that’s actually beneficial because it gives teachers an authentic picture of what your child truly understands and helps them better support your child’s learning progress.

Common Concerns, and What the Research Says

As parents, it’s natural to wonder whether your child might feel confused or struggle to learn a new language when it’s not spoken at home. Here’s what research says about some common misconceptions:

Will my child be confused by the two languages?

At first, it’s normal for children to be a bit confused as they learn to switch between different grammar structures and use different languages with different people. According to Rachel Cortese, a former speech-language therapist at the Child Mind Institute, these mix-ups are a normal part of learning two languages (Cortese, 2025). Many bilingual children use words from both languages in the same sentence, a process known as code mixing. This isn’t confusion, rather it’s a natural strategy to express themselves using all the words they know. If a child can’t find a word in one language, they’ll simply borrow it from the other. It’s a sign that your child is taking the “path of least resistance” (Byers-Heinlein & Lew-Williams, 2018).

Is it too late to start?

Never! While earlier exposure can make language learning feel more natural, age is not the only factor. Language learning depends on natural ability, experience, motivation, consistency, and effective teaching methods. In fact, older children often have stronger focus, better memory and metacognition, and more tools, like visualization techniques and study systems, to support learning. Although accent and fluency may vary, language learning at any age offers significant benefits, including greater memory retention, problem-solving skills, and cognitive flexibility. Bilinguals also gain valuable social benefits, such as stronger perspective-taking skills and smoother cross-cultural social interactions and understandings (Woodall, 2024). It’s worth noting that, historically, American society promoted monolingualism, believing that learning or using a language other than English would hinder assimilation. Native language use was often discouraged in an effort to conform to mainstream culture. In response to growing diversity in schools and modern research highlighting the cognitive, academic, and social benefits of bilingualism, there has been a shift toward encouraging children to learn multiple languages, leading to a stronger emphasis on bilingual education today (Goldenberg & Wagner, 2023).

Early experiences play a powerful role in shaping language abilities. Studies on language acquisition have shown that language development is, in part, influenced by a critical period, a time period during which the brain is particularly sensitive to linguistic input from the environment. While researchers have not identified an exact start and end point for this period, many agree that it extends until puberty, suggesting that the earlier a child is exposed to a new language, the better. After this critical window, the natural ability to acquire a new language fluently gradually declines, making it more challenging to achieve native-like proficiency (Purves et al., 2001). Early exposure to a second language allows the brain to take advantage of its heightened plasticity and sensitivity to different sounds, accents, and linguistic input, making it easier to pick up a new language naturally (Byers-Heinlein & Lew-Williams, 2013).

Will my child fall behind in English?

Bilingual children are no more likely than monolingual children to develop language delays or to be diagnosed with a language disorder (Byers-Heinlein & Lew-Williams, 2013). When children learn two languages at once, however, they might experience a brief vocabulary or grammar lag compared to monolingual peers. However, research shows bilingual children typically catch up by around age 10 (Hoff & Core, 2016). It’s also worth noting that bilingualism strengthens key academic and cognitive skills, such as math reasoning, literacy, attention, and executive functioning, while promoting the ability to think more flexibly and abstractly (Bialystok, 2001).

Your support, whether through direct practice or by providing opportunities for engagement, is invaluable! Every child can successfully learn a new language, even if it isn’t spoken at home.